Introduction

The 1960s Dutch commercial slogan “one egg-meal per day” referred to the purported healthy consumption of eggs. But flashy food advice tends to have a very short lifespan.

In the 1970s, the cholesterol hype emerged, and the advice was to limit egg consumption to one or at most two per week, due to cholesterol and the associated risk of cardiovascular disease.

Cholesterol has long since ceased to be the spectre it once was. And rightly so.

So, do we need to deploy another bogeyman to keep citizens away from eggs, especially those from ‘home-raised’ chickens? Seemingly.

The free-range chickens in the garden are apparently getting ’too much’ PFAS.

In summary: ‘start the day, don’t crack your own egg but buy one from the store’ as suggested by the RIVM (I’m paraphrasing). Reason: much less PFAS in store-bought eggs. Imagine people being able to take care of themselves. The idea!

By the way, this was attempted before in 2014 with an oldie but goodie: dioxin.

Anyway: another round of PFAS is on the menu, because we have a ’new fear winner’ announced right before Easter no less. How convenient.

PFAS: what are they again?

More than two years ago (!), I reported extensively on the PFAS ‘plandemic’ to my valued readers, that is the newest ‘orchestrated anxiety disorder.’ There’s still nothing new under the sun: fear sells, especially of the chemical variant.

Anyway, what again are PFAS?

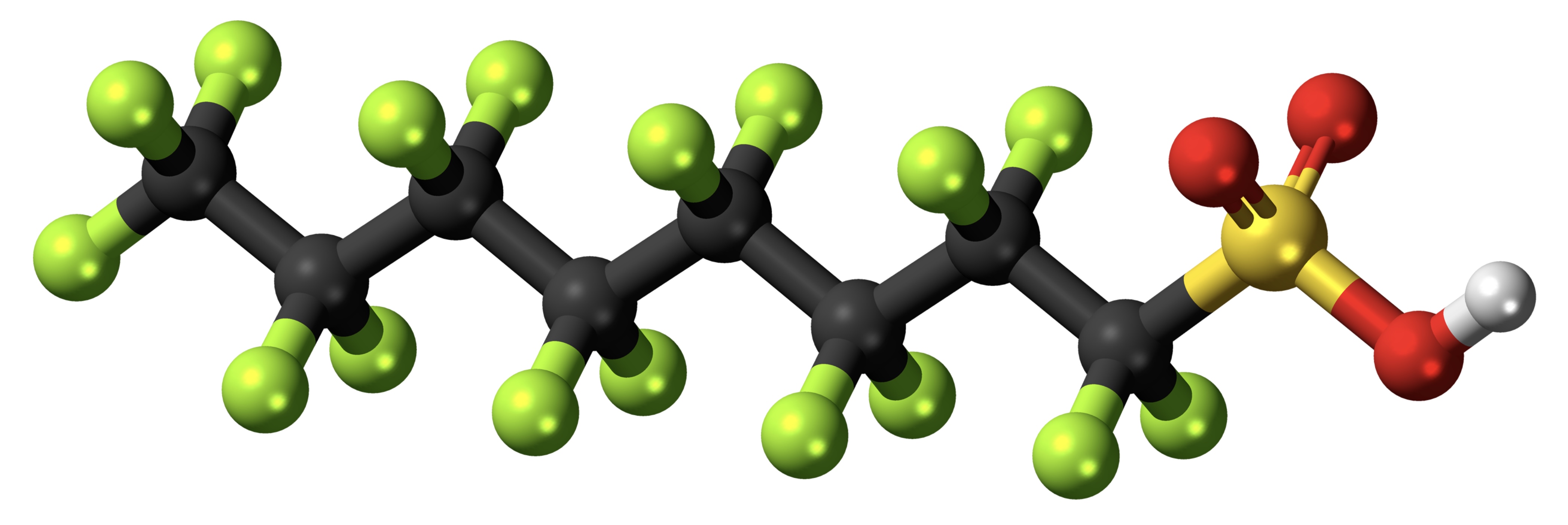

PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a group of chemicals that repel both water and fats (oil). They are carbon compounds where the normally present hydrogen atoms (H), connected to carbon atoms (C), are replaced by fluorine atoms (F). An example is perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA):

The green dots are the fluorine atoms. PFAS are stable compounds. Degradability is relatively low (but certainly not nil); PFAS seem to remain present in our bodies for some time, although half-lives of PFAS are difficult to estimate. PFAS-persistence makes many people worrisome.

Measurability ≠ toxicity

First, the basic principles: detectability is wholly different from toxicity as is persistency, a physico-chemical term. Moreover: toxic substances do not exist. All substances are toxic; only the dose determines whether a substance is not toxic.

This is toxicology-101.

The detectability of chemical substances at increasingly lower concentrations is, by definition, inversely proportional to the toxicity of those detected substances. The lower the concentrations, the more reassuring that is!

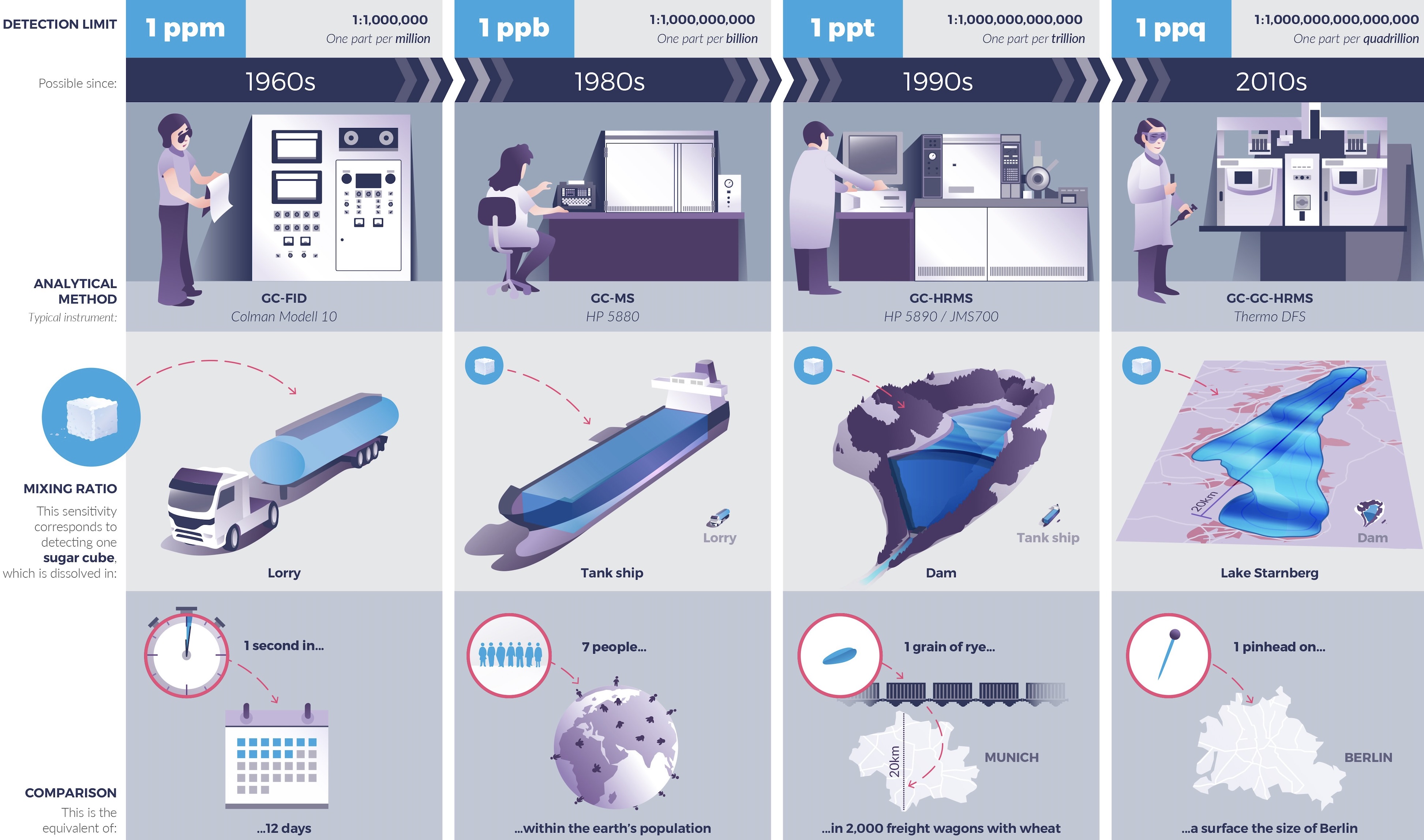

In the 1960s we could detect, at best, sugar molecules from one dissolved sugar cube (±5 grams) in about 15,000 liters of water (parts per million - ppm). Nowadays, we can detect the same amount in Lake Starnberg (Bavaria) with a volume of about 3000 trillion (1 with 12 zeros) liters of water (parts per quadrillion - ppq)

A revolution has taken place in analytical chemistry that is unparalleled. The ‘PFAS problem’ couldn’t even exist 30 years ago since nano-grams were unmeasurable!

The ‘PFAS eggs’ - the poison of ‘over-certainty’

Before we get into (scrambled) eggs, by ‘over-certainty’ I mean the academic arrogance to claim exactitude (in measurements, knowledge, and so on) that simply isn’t there.

The uncertainties in the claims made in the latest RIVM report on PFAS eggs are immense and undiscussed. Per usual I am sorry to say. What’s going on with our ‘backyard eggs’?

First: the ‘health-based guidance value’ (HBGV), as established by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), is set at 4.4 nanograms per kilogram body weight per week based on alleged adverse effects on our immune system.

This EFSA standard (EFSA-4) applies to the sum of four PFAS: PFOA (see above), PFNA (perfluorononanoic acid), PFHxS (perfluorohexanesulfonic acid), and PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid). The EFSA standard is the safety baseline of the RIVM report.

And now, the PFAS quantities in the analysed eggs.

But as so often, the RIVM report disappoints: raw measurement data are not provided (Figure 2, p. 22 is just an aggregate of concentrations without mentioning uncertainty of measurement). It’s really high time that all institutions, paid for by the government, do this as standard.

That’s not all, I’m afraid.

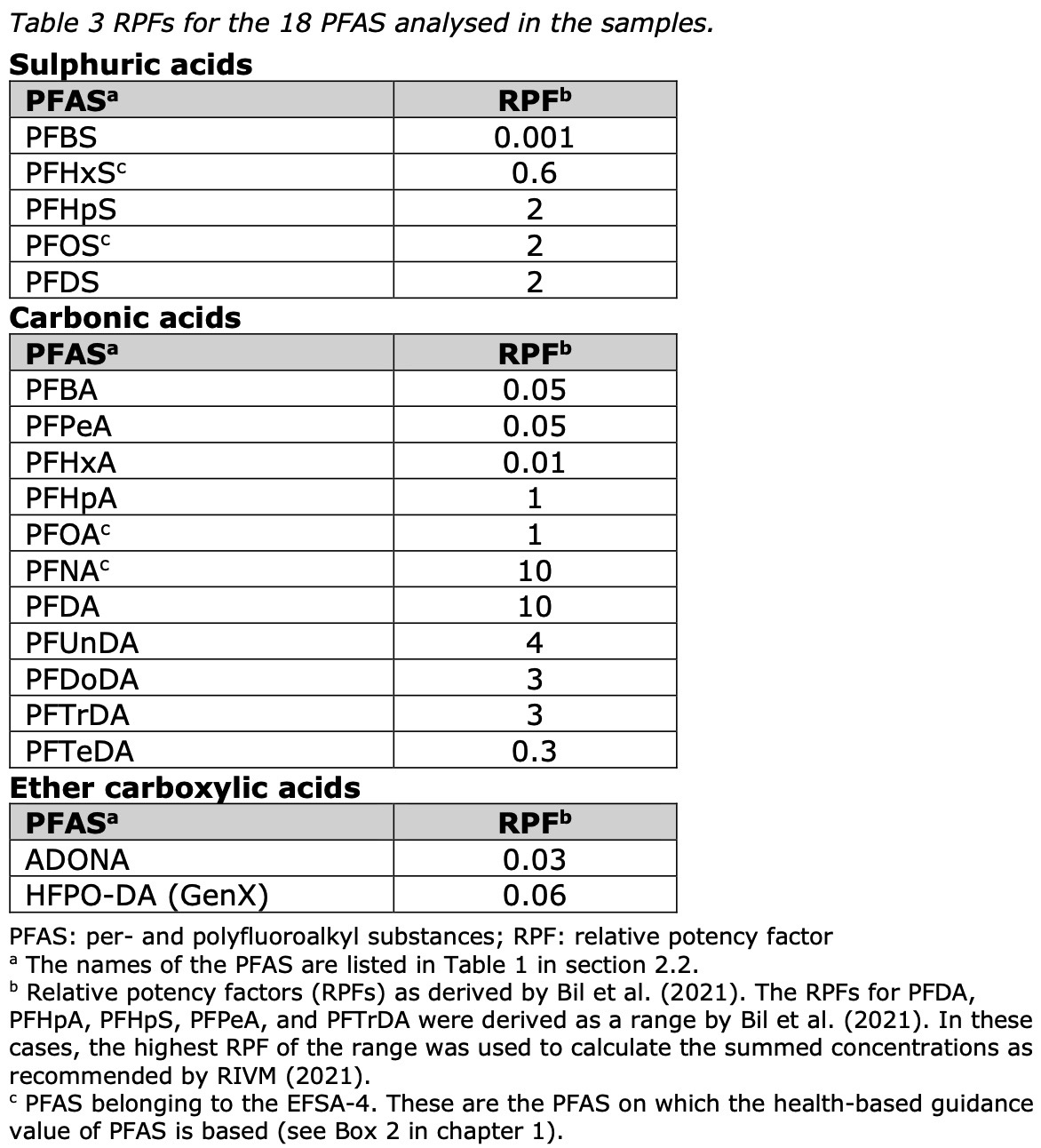

The frustrating part is that instead of actual PFAS-concentrations, PFOA equivalents (PEQ) are employed. That means the found (unpublished) PFAS-concentrations are converted with a relative potency factor (RPF) where PFOA has the toxicity-standard of 1 (RIVM report p. 17):

How does this RPF-system work? Suppose: a sample contains 0.05 ng/g PFOA, 1 ng/g PFHxA, and 0.01 ng/g PFOS. Other PFAS are not detected; those are set at 0 ng/g. The resulting calculation is as follows (see table 3):

- 0.05 ng/g PFOA x 1 = 0.05 ng/g PEQ

- 1 ng/g PFHxA x 0.01 = 0.01 ng/g PEQ

- 0.01 ng/g PFOS x 2 = 0.02 ng/g PEQ

The total ‘concentration’ of PFAS adds up to 0.08 ng/g PEQ. Keep in mind that the EFSA-4 standard is in actual nanograms; not so for the converted PEQs.

The summed recalculated ‘concentrations’ vary, according to the RIVM, between 0.0 - 101 ng PEQ/gram (again: these are not real nanograms!!). And here the problems begin, apart from the fact that the RIVM, numerically, is comparing apples and oranges here.

How accurate are these RPFs exactly? Can a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach be acceptable toxicologically speaking? What is the uncertainty in the determinations of these RPFs? Which toxicological endpoints for the determination of these RPFs were used? Are tested concentrations and animals comparable to humans and in which ways?

And so on.

We need to go back a bit in time to find the RPFs used in the RIVM report: an article by former student Wieneke Bil (with colleagues) provides insight into the establishment of the RPFs.

However, that brings us into even deeper kimchi.

The endpoint of the RPFs used by the RIVM, which were proposed by Wieneke and colleagues, is liver toxicity in rats. The EFSA-4 standard, however, is about immune toxicity. Big difference.

I’ve checked the PFAS doses given to rats, and these are not small. Au contraire.

Across different PFAS and experiments, the doses vary between 0.03 - 1000 milligrams/kg body weight! Most experimental doses thus are far beyond human exposures.

Also: if Wieneke and colleagues propose an RPF range in their 2021-study - for example, for PFHpS, 0.6 ≤ RPF ≤ 2 is reported - the RIVM-report chooses 2. Safety first, right?

However, Rietjens and colleagues, in typically soothing academic vernacular, provide a scathing review of the RPFs, and rightly so (my translation):

“However, we argue that the recommendation to use the RPFs proposed by Bil et al. (2021) in risk assessment and risk management strategies is difficult to defend. …

With respect to the robustness of the proposed RPF values, Bil et al. (2021) indicate that the proposed values are based on liver toxicity in rats and that it may be relevant to validate whether they are relevant to other endpoints. This is important given that the EFSA TWI is based on an immune effect in humans as the critical effect.”

Wieneke and colleagues have responded to this and other criticisms; I’m not impressed. And we still haven’t addressed the uncertainties in the RPFs and the eggs (the raw PFAS data).

These are legion and not discussed and not accounted for: neither experimentally (the rat experiments and detected PFAS quantities in the eggs), statistically, nor in terms of modelling, and so on.

This is the academic poison that destroys virtually every (public health) debate: ‘we’ are so certain of our case that in this instance “the RIVM gives the general advice not to eat homegrown eggs.”

And to think that the evidence for the danger of PFAS to our immune system is downright dubious. That much is clear from the most recent studies on the subject.

The ‘poison of academic over-certainty’ is the true health-underminer.

And …

Well, how ‘PFAS-dangerous’ are our backyard eggs? Let me answer this question as follows: if there are people who still have fresh backyard eggs, I’m the first person to take them off your hands (happy to pay for it)!

The biggest danger is that I mess up in the kitchen, that is burning my ‘famous’ scrambled eggs to a crisp.

Eggs are an excellent (and relatively inexpensive) source of numerous nutrients! This also applies to the backyard varieties. In short: enjoy your egg-meal. Cheers!