Aan het onderwerp toxicologie heb ik een klein aantal blogposts gewijd in het verleden. Deze bijvoorbeeld: Gehalogeneerde angst: PFAS, bodem en volksgezondheid

We zouden het veel vaker over de toxicologie, de leer der giften, moeten hebben. Het speelt een hele belangrijke rol in ons leven en in de samenleving.

Denk maar aan het melamine drama dat de NVWA heeft veroorzaakt.

Het is een klassiek voorbeeld waarin met ’een beetje’ toxicologie, en de kunst van het weglaten, mensen bang worden gemaakt met ‘giftige stoffen’ die uit een bepaald soort kunststof in ons voedsel zouden kunnen komen.

Wat deze coronatijd ons heeft geleerd is dat angst een zeer effectief instrument is om mensen en de samenleving gevangen te houden in wensbeelden van instituties.

Ik zal de claims betreffende het ondermaatse NVWA werk aangaande melamine op een later tijdstip inhoudelijk wetenschappelijk hard maken.

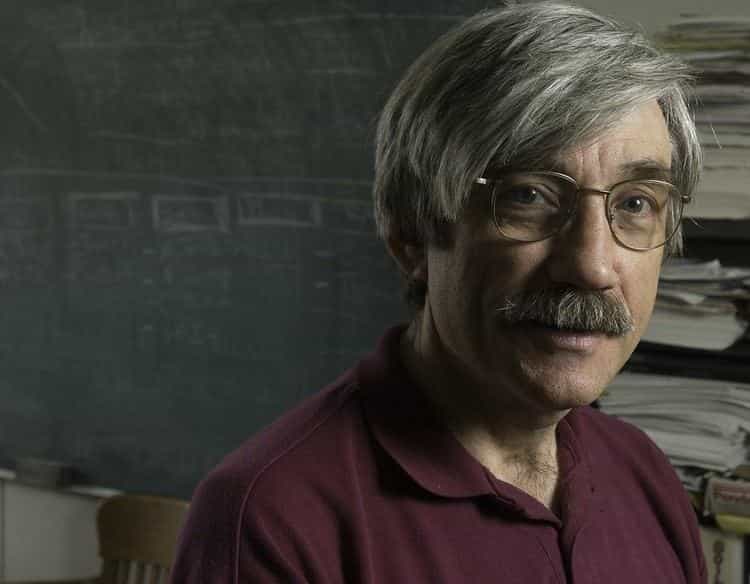

Maar eerst laat ik vriend en collega prof. Edward Calabrese, geen onbekende in de toxicologie, aan het woord in deze blogpost.

Daar ben ik zeer verguld mee; dat moge duidelijk zijn. Zijn bijdrage, in het Engels natuurlijk, staat hieronder.

“We are bombarded incessantly by chemicals. Primarily via our diet, mind you. And the following question always looms beneath the surface: can one single molecule seal our fate because of its cancer-inducing qualities?

Many scientists actually believe that. The scientific theory, embraced by most in the scientific toxicological community, is known as the Linear no-threshold (LNT).

Let’s try to get our heads around LNT. It is a dose-response concept that is based on the assumption that certain types of biological reactions are directly proportional to dose.

And that is taken literally: all the way down to a single molecule or a signal ionization due to ionizing radiation such as X-rays.

Types of responses are typically mutations … and of course cancer.

And there’s the rub. How safe can we be in a world that inescapably exposes us to many different chemicals, including those that mess with our DNA?

The LNT concept is now about 90 years old. The idea originated from studies in which the investigated exposures were many hundreds of thousand-fold higher than background exposure.

Next, the results of these massive exposures -number of found mutations, number of cancer cases, other disease cases, number of people dying- are to be understood as linearly related to exposures that are much much lower, up to and including the proverbial single molecule.

This concept, in its basic simplicity, is what developed in the field of radiation genetics starting in the late 1920s and has continued to the present day.

Now, why would a belief in linearity have been adopted based on data that are not really very relevant to everyday life?

An odd aspect of this belief is that it is very hard to prove -quantifying the impact of one molecule is beyond anyone’s capabilities- but not very difficult to test ánd discredit.

In fact, even during the 1920s of dose-response concept formulation, there were well-researched studies with publications in highly respectable journals concerning the effects of ionizing radiation and genetic damage/gene mutation that actually contradicted the LNT-concept.

Since there were multiple such non-supportive studies, then how could the belief in LNT be sustained and persuasive?

How many well-conducted experimental studies that were negative were needed to discredit the LNT hypothesis?

The answer must be “not enough”, since the concept was sustained, became a deeply held belief ánd became policy for cancer risk assessment in essentially all countries in the world.

To what extent are such beliefs and policies based on scientific data? Conversely, to what extent are they based on power, appeals to authority and fear?

Recent historical analyses of the LNT suggest that ideological perspectives of leaders in the radiation genetics community during the middle decades of the 20th century lead to ‘modulation’ of the research record, the media, the general public and national governments to affect such policies.

Beliefs in LNT were created, based on distorted scientific claims and profoundly exaggerated fears of genetic- and cancer risks.

That is still the case today, a perspective propagated by regulatory agencies in all countries, who live in self-willed ignorance of the cancer risk assessment history and who continue to create the false demons of fear rather than acting to enhance public health regulatory actions that are more science-based.”

Angst. Voor ziektes zoals kanker en de dood. Als gevolg van de consumptie van een enkel molecuul? En wetenschap die selectief angst kan aanwakkeren. What’s new in the world?

Verlichting begint niet bij de omarming van een wetenschappelijk wereldbeeld, wat dat ook precies moge wezen.

Het begint bij de vraag in hoeverre we zijn bestemd voor slechts het graf of de eeuwigheid en het antwoord dat we geven op deze vraag.

Maar dat is mijn eigen zoektocht, geïnformeerd door het uitstekende werk van vriend Edward, die de controversiële vragen niet schuwt.

Zoals het hoort in de wetenschap!