Al luisterend naar de preek van de aanstaande vrouw van mijn zoon, vandaag gehouden in Bolsward, schoot mij het werk van Jacob Bronowski te binnen. The Ascent of Man.

Een veelgeprezen documentaire uit de jaren 70 van de vorige eeuw waarin een beroemde scene in Auschwitz veel stof deed opwaaien. En nog steeds is deze scene aangrijpend en ontroerend.

Zijn uitspraken in dit fragment zijn juist nu zeer van toepassing.

We zijn zo overtuigd van ons eigen gelijk in menig debat -racisme, klimaat, stikstof, politiek, enzovoort, dat we geen debat meer dulden vanwege ons eigen verpletterende gelijk.

Sterker, we eisen dat elk debat stopt vanwege ons eigen evidente gelijk. Meningen worden feiten; feiten meningen.

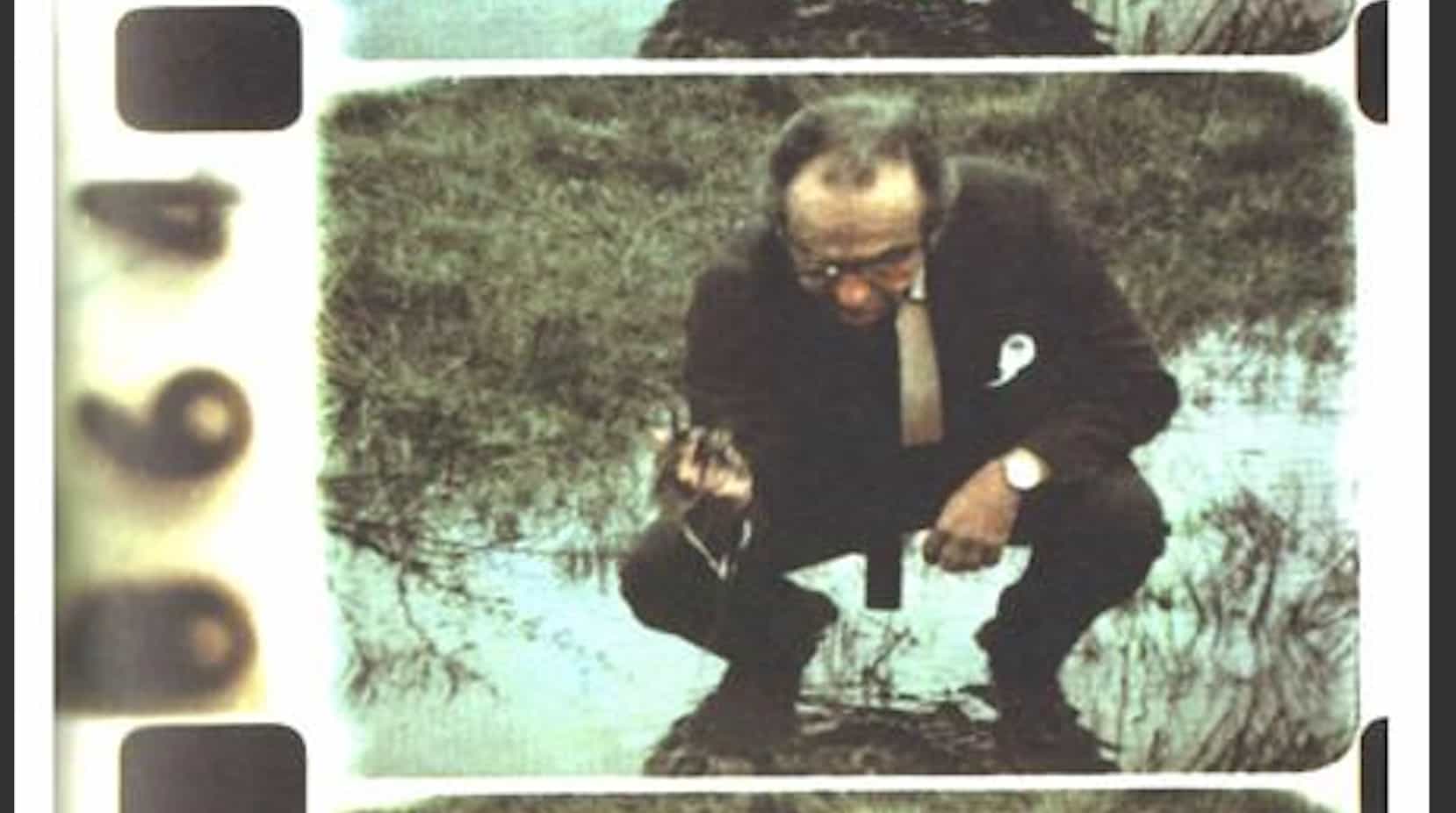

En dan staat Bronowski met zijn mooi gepoetste schoenen in een plas water in Auschwitz, en zegt dit (nadruk toegevoegd):

“There are two parts to the human dilemma. One is the belief that the end justifies the means. That push-button philosophy, that deliberate deafness to suffering, has become the monster in the war machine. The other is the betrayal of the human spirit: the assertion of dogma that closes the mind, and turns a nation, a civilisation, into a regiment of ghosts – obedient ghosts, or tortured ghosts.

It is said that science will dehumanise people and turn them into numbers. That is false, tragically false. Look for yourself. This is the concentration camp and crematorium at Auschwitz. This is where people were turned into numbers. Into this pond were flushed the ashes of some four million people. And that was not done by gas. It was done by arrogance. It was done by dogma. It was done by ignorance. When people believe that they have absolute knowledge, with no test in reality, this is how they behave. This is what men do when they aspire to the knowledge of gods.

Science is a very human form of knowledge. We are always at the brink of the known, we always feel forward for what is to be hoped. Every judgment in science stands on the edge of error, and is personal. Science is a tribute to what we can know although we are fallible. In the end the words were said by Oliver Cromwell: ‘I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken’.

I owe it as a scientist to my friend Leo Szilard, I owe it as a human being to the many members of my family who died at Auschwitz, to stand here by the pond as a survivor and a witness. We have to cure ourselves of the itch for absolute knowledge and power. We have to close the distance between the push-button order and the human act. We have to touch people.”

Elke debat dat de ander dehumaniseert dan wel groepeert onder het kopje ‘vijand’/‘tegenstander’, draagt ten diepste het genocide-gen in zich.

In de cancel culture waart dus de geest rond van de doodswens van de ander die niet ‘bij mij’ hoort en kwaadschiks het zwijgen moet worden opgelegd.

Daarom moeten we mensen (aan)raken, en daarmee aangeraakt worden. The human touch is wederkerig, humaniseert en relativeert.

We zijn allen twijfelend, op de tast, zoekend, totdat de Waarheid Zelf ons aanraakt en geneest.