Het anti-racisme tijdperk is aangebroken, of het was er al en ging het aan mij voorbij (waarschijnlijker). En zoals ik eerder besprak, er kleeft een buitengewoon ongemakkelijk aspect aan dat nauwelijks de aandacht krijgt. Maar er is meer aan de hand, en dat begint met de titel.

Het hemd is nader dan de rok, of zoals ik het duurder formuleer, ‘the law of inverse rationality’. Waar gaat dit over? Kort samengevat: hebben we de moed om de waarheid te spreken, ook als dat heel moeilijk wordt, levensbedreigend zelfs?

Ik beperk mij tot het wetenschappelijk bedrijf.

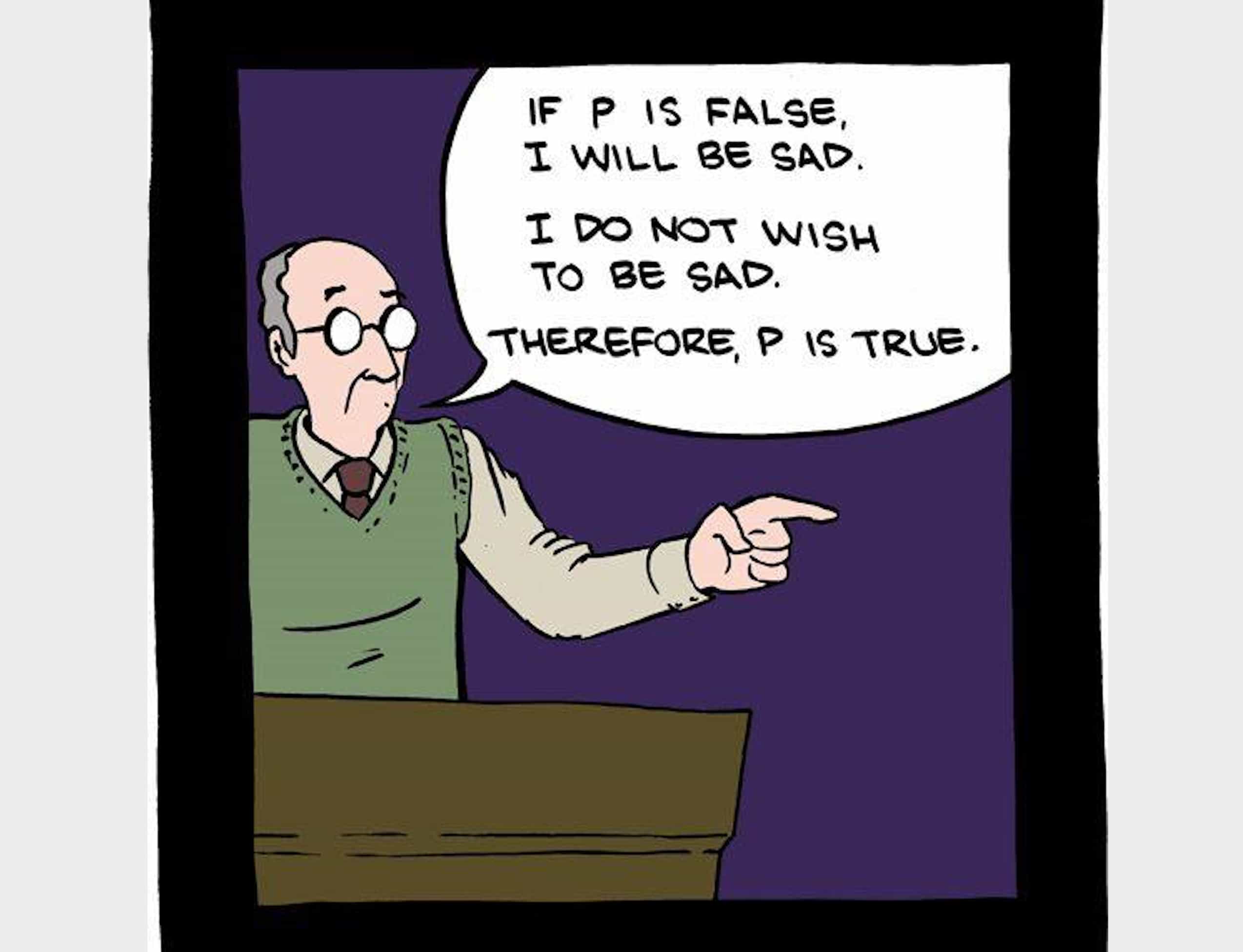

“Wat is waarheid?”, kan heel gemakkelijk worden gepareerd. Dat kan altijd, maar ik zal het een stuk moeilijker maken. Eerst de ‘Law of Inverse Rationality’ (Merold Westphal):

“… the ability of human thought to be undistorted by sinful desire is inversely proportional to the existential import of the subject matter. We can be reasonably rational at the periphery of our interests, where opportunities for prideful self-assertion are limited. But the closer the topic to the core of our being, the greater the tendency to subordinate truth to other values. This has the clear implication that sin’s role as an epistemological category will be especially significant in the areas of ethics and politics, theology and metaphysics.”

Dus, als we gezellig kunnen keuvelen over koetjes en kalfjes, dan staat het feitenmateriaal dat we kunnen verzamelen over deze herbivoren centraal. Er staan geen mensenlevens op het spel, dus kunnen we rustig en met afstand hierover converseren.

Met andere woorden, we funderen ons gesprek op een (moeilijk-woord-waarschuwing) epistemische manier, dat wil zeggen op waarheidsvinding. We wegen dus feitenkennis (voor zover we die hebben) op zoek naar de waarheid over herbivoren.

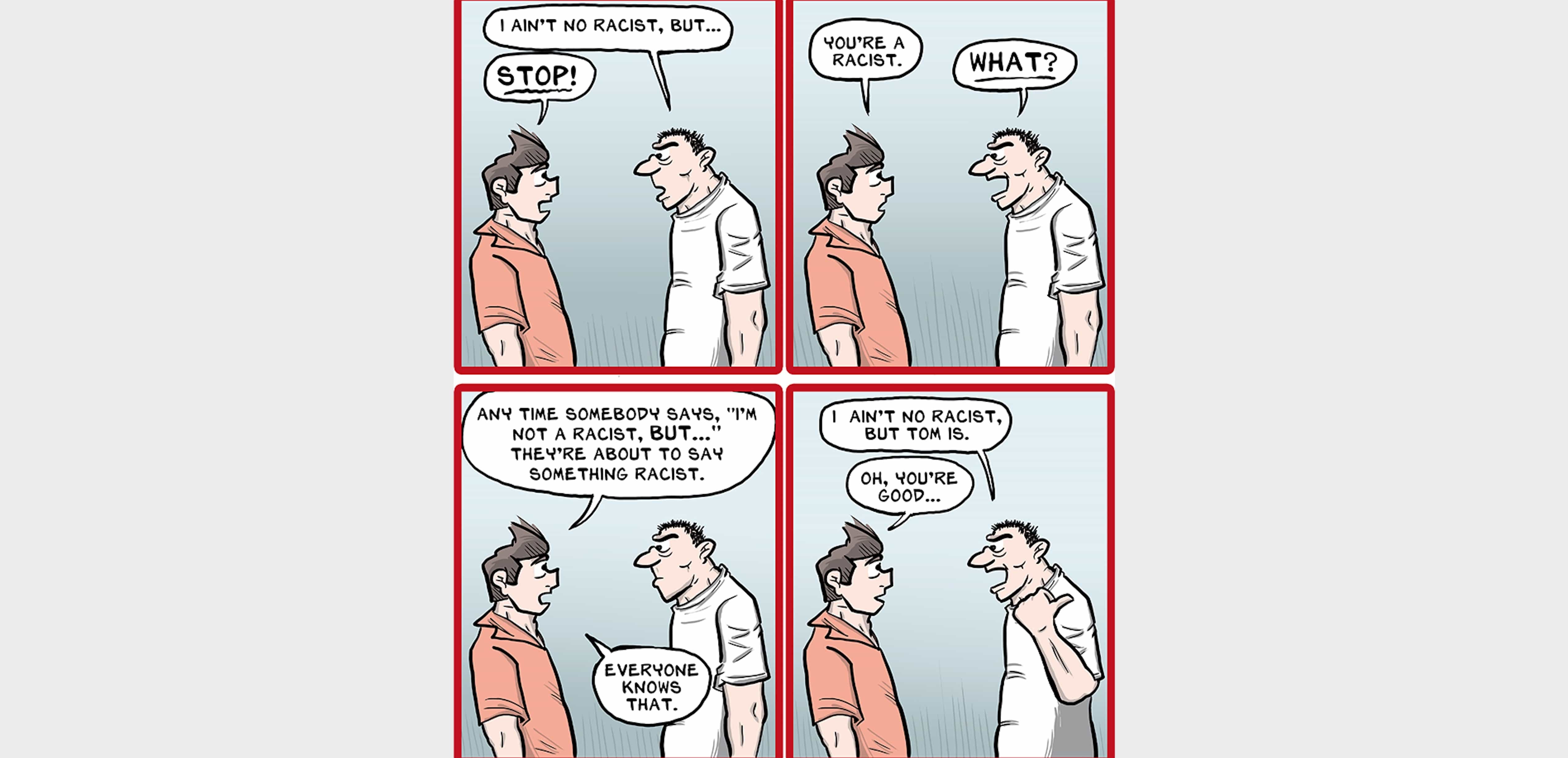

Maar als zaken ons na aan het hart liggen, spelen plots niet-epistemische drijfveren vaak een veel grotere rol dan de feiten die we tot onze beschikking kunnen hebben: lijfsbehoud, geld, macht, aanzien, behoud van een betaalde baan, sociale status, maatschappelijke belangen, jaloezie, openbare orde, enzovoort.

Dus: hoe dichter een onderwerp ons op de huid zit, hoe groter de kans dat de epistemische kant van de zaak ondersneeuwt door de eerdergenoemde niet-epistemische drijfveren.

Laat ik eens een paar pregnante zaken voorleggen (die overigens niet noodzakelijkerwijs mijn interesse hebben):

- Kunnen we het huidige klimaatnarratief feitelijk naar de prullenbak verwijzen?

- Kunnen we gewasbeschermingsmiddelen feitelijk beschouwen als onmisbaar voor mondiale voedselveiligheid en -zekerheid?

- Kunnen we SARS-CoV-2 vaccins (als die er ooit komen) gefundeerd weigeren?

- Kunnen we feitelijk -historisch, politiek, economisch, enzovoort- tot een positief oordeel komen betreffende het presidentschap van Donald Trump?

- Kunnen we feitelijk beargumenteren dat zonne- en windenergie niet duurzaam zijn?

- Kunnen we feitelijk constateren dat racisme van alle tijden, plaatsen en groepen mensen is?

Zal ik een poging wagen de mainstream (grootste gemene deler) antwoorden te geven op deze zes ‘vragen’? Daar gaat ie dan: 1 nee; 2 misschien/nee; 3 nee/misschien, 4 NEE!; 5 nee/misschien; 6 ??.

Hoe moeilijk is het eigenlijk om het epistemische van het niet-epistemische te scheiden en te onderscheiden als onderwerpen ons bestaan diep raken? Heel erg moeilijk.

Zo moeilijk zelfs dat we onszelf volledig voor de gek houden door eventuele niet-epistemische drijfveren, die onze keus feitelijk bepalen, onbewust te verbergen. Ward E. Jones noemt dat de First-person Constraint on Doxastic Explanation.

Juist ja. Dat vraagt een ‘beetje’ uitleg. De centrale term doxastisch heeft betrekking op het waarheidsgehalte van een bepaalde overtuiging, bijvoorbeeld een bepaalde theorie in de wetenschap. Een ‘doxastische uitleg’ stelt feiten - evidence - centraal.

Mijn overtuiging (commitment) dat de aarde een bol is (min of meer), staaf ik alleen met (in willekeurige volgorde): (i) persoonlijke observaties (van velen) dat aan zee de kromming van de horizon zichtbaar is, (ii) verdere feitenkennis verzamelt in de loop der jaren, (iii) foto’s van de aarde gemaakt door de maanastronauten, (iv) basale fysica, enzovoort, enzovoort.

De tegenpool van doxastische commitment benoemt Jones als praktische overtuiging. Bij deze overtuiging speelt de waarheid over de werkelijkheid een ondergeschikte rol.

Het gaat over in hoeverre wetenschappelijke theorieën praktische waarde hebben in het onderwijs, of bijvoorbeeld dat bepaalde ideeën/theorieën maatschappelijke waarde hebben als het gaat over de effectiviteit van de bestrijding van racisme. Maar … (citerend uit eigen werk met behulp van Jones; nadruk toegevoegd):

“The central aspect of doxastic states is that if one reflects upon a belief, one must see it as being held first and foremost to acquire a certain truth. Belief thus has a truth-centred motive. Its possession cannot be dependent on other goals. To do so would undercut the belief. … no appeal to the pragmatic reasons for beliefs can be made in defending a certain position. In no theoretical discourse (e.g., science, philosophy, history) do we find proponents of positions appealing to the pragmatic benefits (e.g. wealth, fame, …, majority position) in order to adopt a certain position. Obviously, a variety of beliefs bring us solace or allow us to make money, but each of these must be seen, and are usually presented, as being derivative of the goal of truth. …

Thus, practical arguments cannot leave any traces and they must lead to belief (if at all) without the believer being aware thereof. The believer regards his belief about X as acquired solely by epistemic means of deliberations; non-epistemic justifications, if at all present, will remain hidden.”

Dus, als onze overtuigingen primair worden gedreven door aanzien, lijfsbehoud, geld, macht, angst, enzovoort, - de niet-epistemische drijfveren - dan kunnen die nooit worden aangevoerd als bronnen van onze overtuigingen. Dat zou absurd zijn, en terecht.

Maar stel dat ik dat wél zou doen, dat wil zeggen dat ik andere dan epistemische overwegingen aanvoer om een aspect van de werkelijkheid te onderwerpen aan onderzoek. Neem kernsplitsing en -fusie.

Aangezien beide fysische fenomenen hebben geleid to kernwapens, moeten we op grond van die desastreuze consequenties beiden praktisch afwijzen als ondermijnend voor de globale samenleving en de natuur?

Uuuhhh, wat? Dat is belachelijk!

Het is zonder meer waar dat de kennis van kernsplitsing en -fusie heeft geleid tot de meest afschrikwekkende wapentechnologie die de wereld ooit heeft gezien.

Maar dít feit kan niet worden ingebracht om beiden maar als niet-bestaand af te doen. Zoals filosoof Mikael Stenmark opmerkt in zijn Theological Pragmatism (nadruk toegevoegd)

“What seems deeply problematic is that we do not ordinarily think that the truth or the rationality of a belief, model or theory is undermined by its coming into conflict with certain political or moral values. This is presumably because we think that there is no automatic connection between the nature of reality, on the one hand, and our political visions and moral aspirations, on the other hand. Let me give one counterexample from the sciences to bring this out. Scientists believe, for example, that atoms can be split into parts. They also know that this belief was crucial in the construction of the atomic bomb. Some of us think that atomic bombs and other nuclear weapons are evil things and constitute a massive threat to the creation of an ecologically sustainable and peaceful society. Hence, believing that atoms can be split in parts could be regarded as ‘dangerous’ in our time. It would also be seen as ‘encouraging’ attitudes of militarism, control and oppression and under- mining our moral aspirations and political visions. … the question we now should ask is not ‘whether this belief is true or false’, but whether it is ‘helpful in the praxis of bringing about fulfilment for living beings’. Otherwise, it would follow that scientists should try to believe something that has positive consequences for the creation of an ecologically sustainable and peaceful society.

By arguing in this manner, however, we mix factual matters with moral and political considerations. On the contrary, it can still be rational to believe that atoms can be split in parts, even though this belief does not promote a humane world, a non-sexist society and care and responsibility towards all life. The idea here is that the fact that it would be politically or morally desirable that p is the case does not entail that it is true or probably true that p is the case.”

Daarom blijven niet-epistemische drijfveren ten gunste van een bepaalde positie verborgen, althans in het wetenschappelijke discours.

Als ik hardop zeg dat ik iets geloof vanwege financieel gewin, zal niemand mij serieus nemen in mijn overtuiging. En terecht. Ik zou mijzelf niet eens serieus meer nemen.

Terugkomend op de platte aarde, de idee dat ik de opvatting zou hebben dat de aarde een bol is om slechts aanhangers van de platte aardetheorie te jennen, kan nooit overtuigen. Sterker, het ondermijnt mijn eigen overtuiging.

En dát is de First-person Constraint on Doxastic Explanation: hoe duidelijker het wordt dat ik een bepaalde overtuiging heb die gebaseerd is op niet-epistemische drijfveren, hoe groter mijn afkeer voor diezelfde overtuiging.

Of we willen of niet, onze overtuigingen worden nu eenmaal primair gedreven door onze behoefte aan waarheid, hoe post-modern we ook geworden zijn!

Dus: de punten 1 t/m 6 zijn wellicht nog wel te bespreken vanuit het epistemische kader, als we ons best doen en het principe van welwillendheid - een hele belangrijke in de filosofie - ruimhartig toepassen. Moeilijk, maar niet onmogelijk.

Maar als ons leven ervan afhangt worden zaken geheel anders, toch? Dan is het hemd nader dan de rok? Dan is de waarheid zo rekbaar als elastiek. Dan heeft lijfsbehoud toch voorrang op al het andere, de waarheid incluis?

Okay, ik had beloofd de moeilijkheidsgraad flink op te schroeven: als rassenwaan leidt tot de systematische uitsluiting/moord wellicht van groepen mensen, ben ik dan bereid om die mensen coûte que coûte te beschermen?

Wat heeft dat met wetenschap te maken? Alles!

Bedenk dat de eugenetica van ruim een eeuw geleden de hoogste wetenschappelijke accolades kreeg! Zoals Marilynne Robinson opmerkt in haar vlammende kritiek Hysterical Scientism: The ecstasy of Richard Dawkins op Richard’s Dawkins' The God Delusion (nadruk toegevoegd)

“Consider this sentence from his preface, which occurs in the context of his vision of a religion-free world: “Imagine . . . no persecution of Jews as ‘Christ-killers.’” In a later chapter he condemns Jews for discouraging “marrying out” and complains that such “wanton and carefully nurtured divisiveness” is “a significant force for evil.” It is of course no criticism to say that he values the tradition of Judaism not at all, since this is only consistent with his view of religion in general. He seems unaware, however, that there was in fact significant intermarriage between Jews and gentiles in Europe as well as secularism and conversion among the Jews, and that this appears only to have fired the anti-Semitic imagination. While it is true that persecution of the Jews has a very long history in Europe, it is also true that science in the twentieth century revived and absolutized persecution by giving it a fresh rationale – Jewishness was not religious or cultural, but genetic. Therefore no appeal could be made against the brute fact of a Jewish grandparent. Dawkins deals with all this in one sentence. Hitler did his evil “in the name of … an insane and unscientific eugenics theory.” But eugenics is science as surely as totemism is religion. That either is in error is beside the point.”

Afsluitend: het antwoord op de vraag of ik mensen in bescherming neem tegen de heersende waan van de dag stijgt boven de materie uit. Het draait dan om de bereidheid om geconfronteerd te willen worden met de Waarheid. En dan kunnen er twee dingen tegelijkertijd gebeuren: je keert je opponent de andere wang toe én je zet je leven in voor je vrienden.