Vreemde titel. Lijkt niet te kloppen. Het impliceert ogenblikkelijk dat er zoiets bestaat als objectieve moraliteit die ‘boven de partijen staat’. Verwarrend en dus moeten we op zoek naar een antwoord.

En dat leidt tot interessante vervolgvragen die terugverwijzen naar zin en onzin van wetenschappelijk advies. Dat komt later aan bod. Dus geduld wordt beloond.

Maar laat ik beginnen met een persoon van (zeer) groot formaat. Een WOII verzetsheld, biochemicus, Nobelprijswinnaar (1965), en vriend van Albert Camus: Jacques Monod. (Yep, alweer een man.)

Een persoon van politiek, filosofisch en wetenschappelijk statuur. Hij is radicaal in zijn naturalistische (atheïstische) positie en staat model voor velen die wetenschappelijk en filosofisch na hem komen. Even in het kort staat naturalisme voor het volgende (er valt natuurlijk veel meer over te zeggen):

“Naturalism asserts that the world is of a piece; everything we are and do is included in the space-time continuum whose most basic elements are those described by physics. We are the evolved products of natural selection, which operates without intention, foresight or purpose. Nothing about us escapes being included in the physical universe, or escapes being shaped by the various processes – physical, biological, psychological, and social – that science describes. On a scientific understanding of ourselves, there’s no evidence for immaterial souls, spirits, mental essences, or disembodied selves which stand apart from the physical world.”

Mijns inziens steekt Monod met kop en schouders uit boven de huidige atheïstische clan. (Sterker: die kan niet in de schaduw staan van deze man.)

Voor mij is Monod een man van morele onkreukbaarheid. Laat ik dat illustreren aan de hand van zijn beroemde Le Hasard et la Nécessité - La Philosophie Naturelle de la Biologie Moderne (uit de Engelse vertaling; nadruk toegevoegd):

“Modern societies accepted the treasures and the power that science laid in their laps. But they have not accepted -they have scarcely even heard- its profounder message: the defining of a new and unique source of truth, and the demand for a thorough revision of ethical premises, for a total break with the animist tradition, the definitive abandonment of the “old covenant,” the necessity of forging a new one. … In order to establish the norm for knowledge the objectivity principle defines a value: that value is objective knowledge itself. Thus, assenting to the principle of objectivity one announces one’s adherence to the basic statement of an ethical system, one asserts the ethic of knowledge.”

In een boeiende en meeslepende stijl drukt Monod de lezer op het hart de ‘principle of objectivity’ te omarmen als een centrale waarde die leidt tot ’echte kennis’. We moeten breken met alle religieuze tradities, het oude verbond, om dit nieuwe verbond te kunnen verwelkomen. (Over Bijbelse taal gesproken!)

Onomwonden wijst Monod de lezer erop dat we niet bescheiden moet zijn om die, in zijn ogen, nieuwe ethiek de centrale plaats te geven in ons bestaan die het verdient. Zoals hij schrijft in de Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1953 (naar aanleiding van de executie van Ethel and Julius Rosenberg; nadruk toegevoegd):

“As a scientist, I naturally address myself to scientists. Moreover, I know that American scientists respect their profession, and are aware that it involves a permanent pact with objectivity and truth - that indeed wherever objectivity, truth, and justice are at stake, a scientist has the duty to form an opinion, and defend it.”

Dat is duidelijke taal met een hoog moreel gehalte. Er wordt opgeroepen om met compromisloze verantwoordelijkheid te handelen naar waarheid, objectiviteit en recht!

En dat maakt Monod voor mij zo’n ongelooflijk indrukwekkend mens. (Ongetwijfeld zullen zijn oorlogservaringen hem op dit vlak gevormd hebben.)

Toch knaagt het als ik Monod’s positie overdenk. Wat/wie is het dat/die mij oproept om Monod na te volgen in zijn voorbeeld? Hijzelf? Het universum?

Begrijp mij goed: zijn oproep is navolgenswaardig. Dat neemt niet weg dat het niet duidelijk is waarom dat zou moeten. Monod nogmaals in zijn Le Hasard et la Nécessité:

“It is perfectly true that science outrages values. Not directly, since science is no judge of them and must ignore them; but it subverts every one of the mythical or philosophical ontogenies upon which the animist tradition, from the Australian aborigines to the dialectical materialists, has made all ethics rest: values, duties, rights, prohibitions. If he accepts this message -accepts all it contains- then man must at last wake out of his millenary dream; and in doing so, wake to his total solitude, his fundamental isolation. Now does he at last realize that, like a gypsy, he lives on the boundary of an alien world. A world that is deaf to his music, just as indifferent to his hopes as it is to his suffering or his crimes.”

Monod roept ons wakker uit onze wensdromen en confronteert ons met de ‘werkelijkheid zoals die is’: er is niemand die onze dromen, angsten, lijden en misdaden ziet, meevoelt, draagt of onder kritiek stelt. We zijn existentieel alleen. Ongeveer (maar niet helemaal) zoals Keane zingt in Crystal Ball:

“I don’t know where I am

And I don’t really care

I look myself in the eye

There’s no-one there

I fall upon the earth

I call upon the air

But all I get is the same old vacant stare”

En daarmee creëert Monod een onoverkomelijk probleem in zijn analyse. Iets dat symptomatisch is voor het naturalisme. Hij wist dat, maar hij meende daarin geen keus te hebben:

“It is obvious that the positing of the principle of objectivity as the condition of true knowledge constitutes an ethical choice and not a judgment arrived at from knowledge, since, according to the postulate’s own terms, there cannot have been any “true” knowledge prior to this arbitral choice. In order to establish the norm for knowledge the objectivity principle defines a value: that value is objective knowledge itself. Thus, assenting to the principle of objectivity one announces one’s adherence to the basic statement of an ethical system, one asserts the ethic of knowledge.”

Monod’s morele grondslag is objectieve kennis. Het principe van objectiviteit is bij acceptatie daarvan dé morele grondslag waarmee men de geleefde werkelijkheid voorziet van de ’ethic of knowledge’.

Monod begint en eindigt dus op exact hetzelfde punt: datgene wat feitelijk al bestaat -objectief kennen (hoe kun je anders een groot Nobelprijswaardige onderzoeker worden?)- wordt tegelijkertijd de morele grondslag voor datzelfde kennen. Een cirkelredenering.

De existentiële filosofie van vriend Camus laat zich hierin vlijmscherp aflezen. Zoals het slot van zijn Le Hasard et la Nécessité dramatisch duidelijk maakt (nadruk toegevoegd):

“The ancient covenant is in pieces; man knows at last that he is alone in the universe’s unfeeling immensity, out of which he emerged only by chance. His destiny is nowhere spelled out, nor is his duty. The kingdom above or the darkness below: it is for him to choose.”

Wij zijn dus, althans volgens Monod en velen met en na hem, sterrenstof zonder doel, betekenis of inhoud. En dat is gesneden koek voor de meeste moderne filosofen die dat ons steeds voorhouden.

Onze morele waarde, aldus Monod, ligt in de eigen keuze om te willen leren begrijpen. Zijn laatste woorden bij zijn overlijden waren, denk ik, niet voor niets: ‘Je cherche à comprendre’.

Het bijzondere is nu dat de moderne filosofie die Monod, en velen met hem, uitdragen ons juist verhindert om werkelijk te begrijpen. Als er geen zin, betekenis of doel is in ons bestaan en in deze cosmos, dan valt er helemaal niets te begrijpen. Alles vervalt tot het Darwiniaanse imperatief -het begrijpen is onderworpen aan ‘genetisch overleven’- zoals ik eerder constateerde:

“The deep and rarely grasped irony is that those who wholeheartedly defend the Darwinian perspective on, say, good and evil, science and religion and the like, do so not because of some compelling scientific evidence but because they are, by necessity, driven by the Darwinian imperative. They are only promoting their own fitness and reproductive capacity under de guise of science. Mikael Stenmark, in his book Scientism: Science Ethics and Religion drives this point home brilliantly.”

Of zoals de vader van het atomisme Democritus het ooit formuleerde: “By convention sweet and by convention bitter, by convention hot, by convention cold, by convention colour; but in reality atoms and void.”

Deze naturalistische filosofie sluimert overal onder het wetenschappelijke en sociaal-maatschappelijk bedrijf. En dat brengt mij bij de moderne wetenschap en de beslissingen die wij zouden moeten nemen op grond van dit of dat ‘wetenschappelijk feitencomplex’:

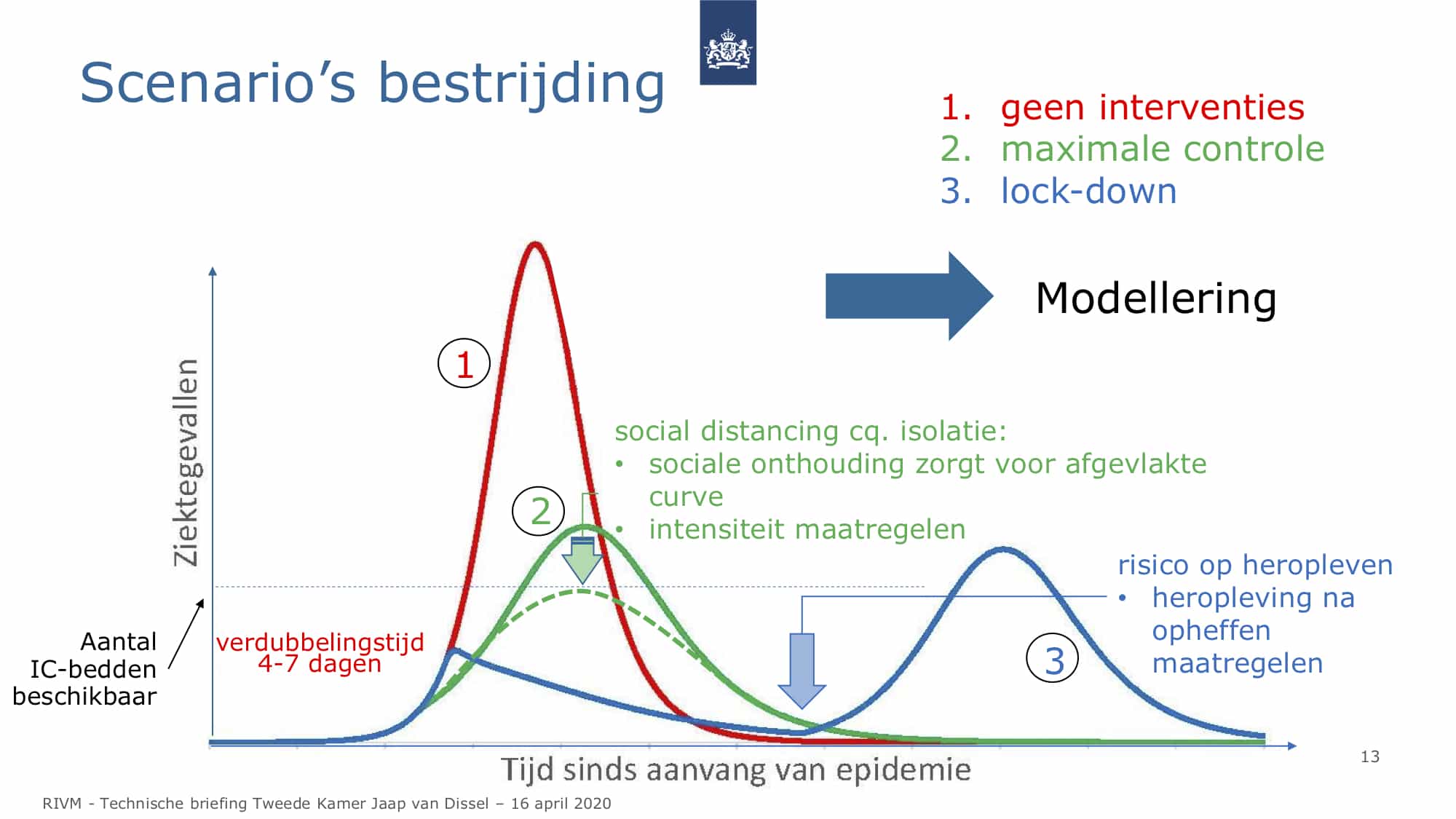

Maar beslissingen nemen op ‘feiten’ is helemaal niet mogelijk, nog los van het feit (pun intended) dat in bovenstaand plaatje helemaal geen feiten worden gepresenteerd.

Het zijn resultaten van modellen, gelardeerd met data, die ook nog eens ‘foutloos’ worden weergegeven. Dat wil zeggen: de onzekerheden staan er helemaal niet in.

(Dat doen de onderzoekers van het RIVM vrijwel altijd om de illusie van ‘zekerheid’ en ‘feitelijkheid’ in stand te houden. Het stelt de politici/media/publiek gerust. Monod is voor hen wat mij betreft verplicht tegengif.)

Maar: waarom is het niet mogelijk om beslissingen te nemen op basis van alleen maar de ‘feiten’?

Simpel (en als eerste): de feiten die we ‘hebben’ zijn verzameld op basis van onderzoekskeuzes die we van te voren hebben gemaakt. Neem een petrischaaltje met bacteriën als ‘simpel’ voorbeeld:

Wat voor aantallen ‘feiten’ kunnen we verzamelen uit dit simpele object met bacterie koloniën? Nou, onnoembaar veel! Een hele kleine selectie: de invloed van het glas op de groeisnelheid van deze bacteriën; welk type bacteriën er groeien; de competitie tussen de koloniën van bacteriën; de oorsprong van de bacterie koloniën; temperatuur invloeden; luchtvochtigheid; UV-straling; bacteriële groeitijd en adaptatie; enzovoort, enzovoort, enzovoort.

Ten tweede. Welke feiten zijn ‘belangrijk’ en welke niet? Anders gezegd: welke feiten geven inzicht ten aanzien van wat precies?

Voordat we überhaupt aan ‘feitenverzamelen’ toekomen, hebben we een serie aan beslissingen genomen van in ieder geval morele -Wat is belangrijk voor ons onderzoekers, het publiek en/of de politiek om te weten? (Ha!)- en technische -Wat kunnen we allemaal analyseren?- aard.

Ten derde. We moeten verzamelde feiten in een verhaal -hypothese, theorie- gieten die we onszelf en anderen vertellen. Anders kunnen we geen chocolade maken van al die losse feiten. Erwin Schrödinger zegt het kritisch in zijn The Mystery of the Sensual Qualities:

“Scientific theories serve to facilitate the survey of our observations and experimental findings. Every scientist knows how difficult it is to remember a moderately extended group of facts, before at least some primitive theoretical picture about them has been shaped. It is therefore small wonder, and by no means to be blamed on the authors of original papers or of text-books, that after a reasonably coherent theory has been formed, they do not describe the bare facts they have found or wish to convey to the reader, but clothe them in the terminology of that theory or theories. This procedure, while very useful for our remembering the facts in a well-ordered pattern, tends to obliterate the distinction between the actual observations and the theory arisen from them. And since the former always are of some sensual quality, theories are easily thought to account for sensual qualities; which, of course, they never do.”

Maar waarom zou dit óf dat verhaal ‘waar’ zijn? Omdat de feiten dat laten zien? Tuurlijk niet. Er kunnen veel verhalen geconstrueerd worden waarin ‘de feiten’ een plaats kunnen hebben.

Maar het RIVM laat één sluitend verhaal zien dat past bij datgene wat de meesten wil horen, zeker de politici: beleid werkt! (Wat een opzichtige treurigheid.)

Sterker, de filosofische God-loze grondslag van ons moderne leven (Monod is daar niet onduidelijk over!) ontneemt alles en iedereen van de illusie dat er zoiets bestaat als een grond om op te staan.

We kiezen zelf die grond/een verhaal en dat opent, onbedoeld, de deur tot een radicaal relativistische kijk op de werkelijkheid: alles kan, als je maar kiest! In Monod’s geval gebeurt dat in absolute openhartigheid. Daar hoef je bij het RIVM niet op te rekenen.

Afsluitend: Monod’s weg is een doodlopende weg. Als exponent van een generatie onderzoekers en filosofen wordt datgene ondermijnt -waarheid, objectiviteit, recht- wat zo noodzakelijk is in deze wereld. Zoals [John Greene]( “Greene, J.C. 1999. Debating Darwin: Adventures of a Scholar. Regina Books, Claremont.”) vlijmscherp noteert (nadruk toegevoegd):

“… In a Darwinian world, reason is of no importance except as an instrument of survival and reproduction, an instrument by means of which the human species has multiplied and achieved dominion over other living beings, only to find its dominion menaced by the very faculty that made it possible. But do scientist really believe that science is valuable only as a means of survival? They do not. The ethos which has guided and inspired science from the Greeks onward is grounded in the conviction that knowledge is valuable for its own sake, that truth ought to be pursued and proclaimed, come what may. The heroes of science are persons … who clung to their vision of truth despite the opposition of popular opinion and the powers that be. But these value judgments make no sense in a world where survival and reproduction are the only criteria of value. …”

Monod was een groot en oprecht mens die op mij een diepe indruk maakt. In weerwil van zijn eigen morele onkreukbaarheid, zet hij met zijn filosofische bespiegelingen, als exponent van een groeiend naturalistisch wereldbeeld, de deur wagenwijd open voor de relativering van wetenschappelijke kennis en kunde, recht en rechtvaardigheid.

Daar plukken we nu de wrange vruchten van. Een beetje orthodoxie van bijvoorbeeld een Gilbert Keith Chesterton kunnen we wel gebruiken in onze tijd:

“Reason and justice grip the remotest and the loneliest star. Look at those stars. Don’t they look as if they were single diamonds and sapphires? Well, you can imagine any mad botany or geology you please. Think of forests of adamant with leaves of brilliants. Think the moon is a blue moon, a single elephantine sapphire. But don’t fancy that all that frantic astronomy would make the smallest difference to the reason and justice of conduct. On plains of opal, under cliffs cut out of pearl, you would still find a notice-board, ‘Thou shalt not steal.’”